Articolo

I. Preface

This article describes an innovative medical curriculum which is being implemented at a new medical school in Colton, California, the California University of Science and Medicine, School of Medicine (CalMed-SoM). In order to better appreciate this curriculum, it is important to understand the characteristics of the medical education system in the United States as well as the structural organization of the new medical school.

Eligibility for admission into medical school in the United States occurs after having attended primary and secondary school for a combined total of 12 years, followed, in most cases, by the acquisition of a Bachelor’s degree, awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting on an average of 4 years. Medical school admission requirements vary from school to school. Some schools require applicants to complete a certain number of premedical courses while in college (i.e. : (a) 1 year of biology, (b) 1 year of physics, (c) 1 year of English, and (d) 2 years of chemistry which includes organic chemistry), while others have moved to a competency-based admission. In addition to these requirements, students are also requested to complete the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) and ultimately go through rigorous personal interviews. Admission is determined on the collective evaluation of all these requirements.

The majority of medical schools in the US have a four year program in which the first two years are usually related to basic science disciplines with the last two years being devoted to clinical disciplines.

The structural organization of CalMed-SoM is composed of one single Department of Medical Education which includes from 2 to 4 content experts from each of the basic science disciplines, as well as clinicians for the clinical skills component of the first two academic years. The number of full-time faculty for the first two, pre-clinical, years number 26 for the initial class of 60 students. There will be a progressive increase in full-time faculty to 28, plus 16 part time clinical faculty for the subsequent class of 90 and a further increase to 30 full-time faculty plus 22 part time clinical faculty, in the third year of operation, when the matriculating class size will reach its maximum number of 120 students/ year. The qualifications of the faculty for the first class of 60 students is presently composed of 47% MD/PhDs, 37% MDs, and 16% PhDs.

The faculty is trained for this new teaching approach by attending faculty-development sessions which com-prehensively cover (a) all of the pedagogically diverse methods employed at the school, and described in this manuscript, as well as (b) the appropriate assessment methods used to evaluate student performance.

II. Introduction

Traditionally, medical degree granting schools throughout the world have utilized a discipline-based curriculum in which students study each discipline as an isolated entity, for example, anatomy, biochemistry, physiology, etc. This approach has been severely criticized for some of the following reasons:

- It creates an illogical separation between the basic and clinical sciences that leads to difficulties in the appropriate application of acquired knowledge.

- The time students devote to acquiring knowledge is considered, to a great extent, to be wasted time since a proportionately significant amount of knowledge is subsequently forgotten or found to be irrelevant.

- The teaching of information that has no apparent relevance to the pre-conceived notion of what students think should be taught in a medical school can be uninspiring and demoralizing, key sentiments responsible for the progressive loss of motivation and enthusiasm.

The realization that there are numerous shortcomings with the use of this curriculum, has stimulated many schools, over the years, to experiment with various curricular reforms. Despite these changes, there is still a general consensus among medical educators that many of the existing curricula have failed to meet the needs of students and, if adequate changes do not come about, will continue to fail the needs of doctors in the future.1

Due to this recognition, the worldwide focus on re-forming and improving medical education continues to occur. Progressive medical schools are working hard to find the best ways to improve medical education so that graduating physicians are solidly prepared to cope with today’s challenges of not only curing but also ca-ring, in an increasingly diverse social environment. It is an awareness reinforced by the recent invitation from the Lancet Global Commission on Education of Health Professionals for the 21st Century1 to correct the major shortcomings of current medical education systems, which they describe as fragmented, outdated, pedagogically static, and not drawing on current educational re-sources. These factors have been blamed to contribute to our current “ill-equipped” graduates.

Just as good medical practice is dependent on good research, so is the improvement of medical education dependent on careful analysis of what works and what does not. While medical schools have experimented with various curricular reforms, there is evidence that the various approaches being used, whether they are based on “disciplines,” “systems,” “problems,” or “clinical presentations” do not have much effect on enhancing student performance2 or ultimate competence in medicine.3 Growing evidence seems to indicate that more important than the type of curriculum being used, is how the curriculum is being implemented.4

In consideration of this background information and the challenges being faced in today’s delivery of medical education, a new medical school is currently being established in Colton, California, with an innovative student-centered curriculum that is an amalgam of the best pedagogy from the most advanced educational institutions around the world. In addition, the curriculum has been refined to correct the major medical education shortcomings cited in the Lancet report.1

III. Overview of the CalMed-SoM Curriculum

The MD program at CalMed-SoM is a system-based, clinical presentation-driven curriculum in which the basic sciences and clinical disciplines have been fully integrated with the clinical presentations (CPs) of each system from the first day of class. Clinical presentations refer to the way each system responds to pathologies, by creating the specific reason (complaint) that a patient presents to a physician; for example, the clinical presentations of the gastro-intestinal system may include “vomiting,” “diarrhea,” “abdominal pain,” etc. The CPs in the curriculum provide the platform onto which basic science and clinical knowledge are both structured and integrated. They are supported by problem-solving pathways in the form of algorithmic diagrams, clinical reasoning guides, and related clinical cases which aid in the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills. The clinical presentation-driven educational program stimulates students to analyze problems, locate and retrieve relevant reference materials from computer-based or library resources, generate hypotheses, and solve clinical problems, while simultaneously setting the foundations for lifelong studying and learning.

The curriculum focuses on a competency-based approach which incorporates diverse methodologies to learning and, draws upon and incorporates global medical knowledge realizing that the practice of today’s medicine has no geographical (ethnic, racial, cultural) boundaries. All the learning methodologies used in the curriculum are guided by adult learning strategies and “active integration.” Active integration refers to a tightly integrated educational system in which every learning domain (i.e. cognitive, psychomotor, affective) in the system, is interrelated to enhance the student’s experience of taking full advantage in the acquisition and critical utilization of the information derived from these learning domains. The aim of “active integration” is to help students to comprehensively address and solve patients’ problems of every possible dimension (i.e., medical, social, environmental) utilizing critical, abductive, deductive, and inductive reasoning. Further-more, all the educational activities which comprise the curriculum have been specifically designed to provide students with the necessary knowledge, skills, attitudes, and feedback to progressively prepare them to effectively perform professional activities without direct supervision (entrustable professional activities) in preparation for their chosen future professional aspirations.

Since the practice of today’s medicine is oriented to-wards a team approach, CalMed-SoM promotes a team-based educational strategy that fosters collaboration, respect, and reciprocal benefits from the views, opinions, and talents offered by members of the team, all aimed at contributing to their scientific and professional education and growth. Through team participation skills, students integrate relevant basic science knowledge being acquired and expound on additional needed knowledge. Through self-directed learning strategies, the students answer structured objectives using analytical and critical thinking skills which evince a complete understanding of the clinical relevance of all the scientific, environmental and social determinants of the clinical problem presented by a “person.”

This new curriculum model has been designated as the “Global Active-Learning Curriculum” which utilizes a Person-Centered Clinical Approach Learning Method (PC–CALMED). The Person-Centered Clinical Approach Learning Method, refers to a combined structured and guided inquiry technique that is applied by students to understand a disorder, problem, or clinical case with emphasis being the “individual” within her/his environment.

This early integration of the clinical and basic sciences creates an important foundation for understanding the fundamental scientific principles governing excellence in medical practice. Its relevance also reinforces, and keeps alive, the drive to become physicians that had initially motivated students to apply to medical school.

IV. Colleges

Another key component in CalMed-SoM’s curriculum is its team-based educational strategy, mirroring the current trend towards a team approach in the practice of medicine. As described above, the team-based educational approach fosters collaboration that is critical in enhancing both scientific and professional education as well as, ultimately, sustained professional and personal growth.5 The “teams” at CalMed are created within “colleges” which are defined, in traditional Latin, as a formal group of colleagues working collaboratively together, to reach particular goals from which each member can benefit.

At CalMed, each “college” is composed of ten students guided by two mentors, one from the basic science faculty, one from the clinical faculty. The ten students are then divided into two teams of five students each. Teams are composed of students with different learning styles, different approaches, different affects, and different learning characteristics, helping all students learn within the framework of diversity, allowing each team member to share knowledge from a different perspective, enhancing learning and personal growth.

One novel approach at CalMed is that each College is given a dedicated meeting room where all their college-based educational activities take place. One of the first tasks that the students of each team have is to choose a name for their College from the many scientists and artists who have contributed, throughout history, to the advancement of the arts and sciences. This, along with the introduction of an historical anecdote in every lecture (see “Classroom Discussion Sessions”) supports CalMed’s aim of ensuring that their graduates are not only scientifically astute, but also culturally competent physicians with a global world view.

V. Pre-Clinical Years

1. Naming of Courses

In its desire to break away from medical school traditions that have impeded optimal medical education, CalMed is also breaking away from the use of traditional course names that often reflect a lack of appreciation of the human body as a coordinated entity. CalMed’s courses use names that indicate a more profound appreciation of the influence of art on science and science on art, as well as the complex interrelationship of all bodily functions. Traditional medicine sees, for example, the gastrointestinal and cardiovascular systems as succinct, separate entities; CalMed understands that these systems, like all functioning parts of the human body are interrelated and interdependent. In other words, Cal-Med employs a holistic approach. Course names, listed in Table 1, reflect that appreciation.

2. Organization of Courses

Each system-based course has an appropriate course length to cover all of the necessary learning objectives.

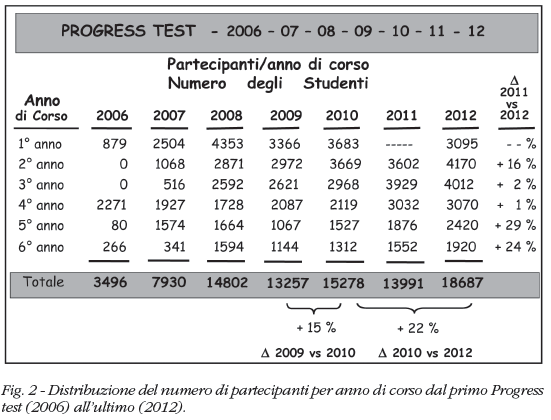

Figures 1A and 1B depict the sequential distribution of the courses in the pre-clinical first and second years. In addition, the educational environment as well as the curriculum have been designed with the aim of enhancing successful academic progress. Rather than have courses considered as hurdles to overcome, CalMed has designed a curriculum that encourages learning and retention, helping to eliminate poor course performance and thus the need to remediate. To promote this objective, the organization of each course has been designed to stimulate the student to learn and keep up with the daily educational activities and, by placing a week at the end of each course, time is dedicated to a final re-view before taking the summative examination (Figure 2). This exam week gives students the opportunity to attend an instructor-led review of the entire course. During the review, instructors will go over the essentials for each discipline. The format used is determined by each instructor, and can vary from a “flash card” approach to more detailed but concise presentations. The second and third day of the week are set aside either for student review or, if necessary, to get individual help from the faculty. Exams that cover all the material taught in the course, including clinical skills and laboratory procedures, take place on Thursday and Friday.

3. Organization of Each Week’s Educational Con-tent

A typical week during the first and second year at CalMed is depicted in Figure 3. During this time, teaching is geared toward promoting “active learning,” that is, encouraging students to take an active role in the educational process rather than being passively taught. This is in sharp contrast to the traditional styles of teaching, where students are expected to sit for hours, listening, and theoretically, absorbing the information presented by the instructor, the so-called “sage on stage.” In active learning modalities, which CalMed utilizes, the instructor facilitates critical learning skills, rather than forcing students to listen passively to lectures, ergo “the guide on the side.” This approach has been shown to promote independent, critical, creative thinking, to increase student motivation, to improve performance, and to encourage effective collaboration. For these reasons, active learning strategies have been incorporated into every component of CalMed’s educational activities.

3.1. Classroom Discussion Sessions

Classroom discussion sessions are shown in Figure 3 by the boxes indicated by the letter “(A)” (i-RAT and t-RAT sessions) as well as the boxes indicated by the letter “(B)” (flipped classroom sessions). These sessions, as denoted in Figure 3, take place on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays. In preparation, students are asked to review voice-over PowerPoint lectures available on the intranet for at least fourteen days prior to their discussion in class. Topics and lecture titles are listed in each course syllabus. This is illustrated in Table 2, which is an excerpt from “The Scientific Foundations of Medicine” syllabus that covers the first week of the course.

a. “Lectures” (Voice-Over PowerPoint Lectures)

Each lecture has a maximum length of thirty-five minutes and its preparation by faculty is composed of the following four sections:

Section 1. The very first slide of the lecture instructs students to study the lecture well in advance of the class in which it will be discussed, preferably reviewing it the day before the discussion. This slide also indicates the date the lecture is to be discussed. Students are instructed to write down questions they may have, or topics relevant to the lecture that they would like to discuss during the “discussion session,” in the presence of the content expert. These questions would then be given to the student-selected team leader during a team meeting, prior to the class, where the questions are prioritized according to their level of importance.

Section 2. The lecture proper begins with a slide indicating the title of the lecture, followed by one or, at most, two slides, depicting an historical reference to the subject of the lecture. While this is innovative, because “history” is rarely an expected part of medical school lectures, the first impression of today’s students is to see “history” as being boring and a distraction because they are focused on what they envision as being practical and directly relevant to their future profession. Despite this student impression, the teaching of medical history continues to be considered highly useful but probably best learned in context, as part of the background to basic science disciplines and clinical studies, instead of being taught as a separate course as once existed in the vast majority of medical schools. It has been shown that historical perspectives keep students engaged, in addition to provoking in-depth thinking about the sequence of medical progress. By being a window into the past, “history” not only provides an appreciation of what has been done before and its influence on medical advancements, but also helps students understand that medicine is a continuum of improvement in which they too can play a part. It has been shown that expo-sure to historical information spontaneously stimulates students to develop and employ reasoning and critical thinking abilities.6

Section 3: This section comprises the body of the lecture. It is introduced by a slide that outlines three to five session learning outcomes intended to be reached by the end of the lecture. At the end of each section of a particular topic of the lecture, a bibliographical reference is included in the slide for students who wish further clarifications.

Section 4: The last slide of all lectures presents a brief clinical case, which nevertheless contains all of the traditional components, for example “chief complaints,” “history of present illness,” “past medical history,” “social history,” “family history,” “review of systems,” “physical examination,” and, if appropriate, “results of investigations.” Two to four questions embedded within the clinical case help to trigger appreciation of the basic science content of the lecture. The questions are exclusively for the benefit of the students to see if they have understood the basic science concepts presented in the lecture and their clinical relevance. The slide of the clinical case at the end of each lecture further serves to ingrain the clinical vocabulary used in describing all the pertinent information that a physician needs to arrive at a diagnostic decision and management plan.

The instructor, as the content expert responsible for a specific lecture, prepares five multiple choice questions (MCQs) that address the learning objectives/outcomes of the lecture and that will be used for formative and summative examinations. The instructor also prepares a list of questions which address concepts that are believed to be essential that students clearly understand, in the event that the students do not raise such question in the “flipped classroom” discussion session, described below.

b. i-RAT and t-RAT sessions

At the beginning of each day in which classroom discussion sessions are held, students take an individual readiness assurance test (i-RAT) that covers previously assigned material. The i-RAT is constructed using two of the five previously prepared MCQs from each lecture. These tests hold students accountable for learning the material before the class discussion. Once submitted, they are graded and eventually returned to the student as feedback.

Immediately after taking the individual test, students retake the same test as a team (t-RAT). The team effort provides an exciting opportunity for students to learn from one another, and help each other in a positive team effort. During the joint session that follows, each team leader, when requested by the instructor, collectively display to the entire class their answers with the use of an audience response system. The instructor provides the right answer and calls on teams to explain the rationale for their selection. By this process, not only are answers corrected, but reasons for misconceptions are uncovered, which may sometimes reflect problems in the construction of a question. While the team effort for learning is paramount, faculty are always available to help students understand and master difficult material.

The use of i-RATs and t-RATs that CalMed-SoM utilizes in all its system-based courses, is supported by studies that have shown that repeated testing improves long-term retention of material,7,8 and that retention is further increased when feedback is also furnished.9 Furthermore, psychology-based research indicates that taking quizzes and tests can reduce the “forgetting curve” by utilizing “retrieval practice,” another aid to retaining information.10

c. Flipped Classroom Discussion Sessions

The term “flipped classroom” refers to a pedagogical model that draws on such concepts as active learning and student engagement. It describes class structures that include pre-recorded lectures, which act as the homework element, followed by pertinent inclass activity. The value of this model is that class time is viewed as a time when students can question the content of a lecture, and test their skills in applying the information received, while interacting with one another. During these sessions, the instructor functions as a positive facilitator.

In contrast to the flipped classroom, the traditional class lectures are characterized by students trying to write down everything they think they need to remember without having the time to either reflect on what is being said or write everything that is being said, leading to the likely possibility that important information may be missed. The use of pre-recorded material, on the other hand, places the lecture under the control of the student who can watch it as many times as it is necessary to fully comprehend its content.

Before coming to class, each team has met to re-view, discuss, and finally collate those questions which have been raised by individual team members, as they reviewed the lectures, but have not been satisfactorily answered within the team. Collaborative interaction among the members of a team facilitates learning from one another as well as helping each other.

The structure of the class is as follows. Each team’s leader poses the team’s first question to the class and wait for an answer from other classmates. The determinant of the accuracy of the answer is the instructor. If the question has not been answered to the satisfaction of the instructor, a call is made to other classmates to complete the answer. The instructor intervenes only if no one can answer correctly or complete the answer. This routine continues, in a rotating fashion, by each team until all teams have asked the most important questions on their list, continuing until the two to two-and-a half hour time limit has been reached. This pedagogical model brings about an important change in traditional educational priorities by moving the emphasis from simply covering the presented material toward mastering that material.

3.2. Small Group Sessions (SGSs):

Small group sessions using Short Case Versions of PBL are considered an ideal educational model for learning how to successfully apply hypothetical inductive reasoning and expertise in multiple domains. Clinical cases that match a specific week’s clinical presentation theme are chosen for that week’s small group sessions. The contents of these clinical cases include learning triggers that are appropriate for that week’s course instruction. For each case, the list of established learning objectives, as shown in Table 3, cover the required components of knowledge, skills, and attitude necessary for students to master.

a. Organization of SGSs

Two structured small-group learning sessions, each two hour long, are held each week. The first, “Small Group-Session 1,” is held on Monday and the second, “Small Group-Session 2,” is held at the end of the week, as indicated in Figure 3. The structural organization of the SGSs reflects the composition of each College class, i.e., 10 students per college room, corresponding to two teams of five students each. Learning takes place concomitantly through self-study as well as through mutual “team” support. While the environment is student-centered and self-directed, a faculty member is available to facilitate in the clinical reasoning sessions as necessary.

Session 1 is held in a large classroom that accommodates the entire class. Each team of first year students is provided with one clinical case, whereas second year teams are provided with two cases. Each clinical case has a presenting complaint, reflecting one of the approximately eighty different “clinical presentations” which is scheduled for each week of the system-based courses during the first two years of the curriculum. Each clinical case contains information related to the following:

- presenting complaint and history of current illness; b) personal, family and social history; c) review of systems; d) physical examination; e) initial laboratory/ imaging studies (if appropriate).

An algorithm (an example of which is given in Figure 4), delineating the clinical presentation, is given to the students and explained by the clinical instructor with the aid of a clinical reasoning guide. After this presentation, the students, referencing the algorithm, “brainstorm” in teams, facilitated, if necessary, by their college mentor. This initiates the process of (a) analyzing the clinical problem, (b) clarifying the terms used and concepts presented, (c) identifying issues or “key points” with the goal of finding appropriate explanations, (d) addressing learning needs, that is, what new information/knowledge is necessary to achieve the learning objectives, and (e) identifying and discussing issues raised by the learning objectives. The learning objectives/outcomes for all clinical cases, which guide the work of the teams, are indicated in Table 3. This process strongly supports self-directed learning as students identify gaps in know-ledge, plan appropriately, then search for, collect, and discuss, the needed information.

During the week, students listen to, and review, the pre-recorded lectures, and attend the flipped classroom sessions where faculty-supported discussions address the systems/topics/problems involved in or related to the case of the week. On a regular basis the teams also meet to integrate theory and practice, working together to develop a reasoned solution to a complex problem, thereby answering the questions raised by the learning objectives.

Session 2, takes place at the end of the week in assigned college rooms. Through oral and/or Power-Point-driven presentations, students share the knowledge they have accumulated by providing answers to the questions related to the learning objectives/ outcomes. Each member of the team is expected to be familiar with the entire presentation and, therefore, prepared to present any of the five learning objective/ outcomes (Table 3). The college mentor, prior to the presentation, will determine the pairing of the student with the specific “section” to be presented. The presentations and the submitted answers will be evaluated and considered as formative assessments (with appropriate feedback) throughout the course, except for the last two weeks, where they will be evaluated as summative assessments. Final student evaluations will result from student self-evaluation, peer evaluation, and faculty evaluation of students’ presentations and performances.

3.3. The “da Vinci” College Colloquium Course

The “College Colloquia” are longitudinal courses that extend throughout the first two years and are held for two hours each week. Figure 3 identifies the location of the course in each week’s academic calendar. Each course is composed of two modules, exemplifying the “art and science” components of medicine. The first module is the college colloquium proper that is designed to help transform medical students into expert practitioners with sound professional behavior and empathy, in keeping with the epitome of great healers throughout history. At the heart of the courses are examples of the ethics and values that are emblematic of greatness in the medical profession. These colloquium sessions are interrupted every third week by a Journal Club module, which is the more scientific-related component of the Colloquium experience, as described below.

The college colloquium courses address the art and science of medicine from both a philosophical and analytical perspective, examining them as they relate to the social determinants of health, especially the challenges of global health. In that regard, these courses focus on individual health and well-being as well as on “Population Health, “Planetary Health” and “One Health” with an emphasis on prevention, promotion, and maintenance of good health.

a. College Colloquium Sessions

The colloquium is designed to explore medical humanities and complex areas of controversies including universal health care access, social determinants of health, differing moral values in different societies, end of life issues, organ donations and trade, and the caveats to providing accessible quality healthcare for entire societies. In addition, the colloquium is designed to address many educational and professional themes including the promotion of critical thinking, moral and ethical behavior, reflective mindfulness, respect, empathy, and understanding the importance of being socially accountable members of society. The sessions will also focus on the multidisciplinary aspects of healthcare and on the goal of lifelong personal and professional development.

The educational learning approach in the “College Colloquium” sessions utilizes the strategy of “cooperative learning”11 which, among other things, has been shown to enhance reasoning skills and improve self-esteem.12,13 Seven educational techniques have been selected to fulfill the intended aims of each session. These techniques include: (a) Think–Pair–Share14 (b) Discussions (“reciprocal teaching”)15 (c) Debates (d) Student

Teaching, also knowns as modified “reverse jigsaw” (e) Role Play (f) Team Game Tournament,11 and (g) Problem solving, using clinical cases.

b. Journal Club (JC) Sessions

The Journal Club meets specifically to assess and critically discuss the strengths and limitations of a scientific publication. Generally, the number of Journal Club sessions held in each system-based course is dependent on the duration of the course. The ultimate goal of the Journal Club is to help lay the foundations for critical, lifelong, self-directed medical education by encouraging the analysis of published peer-reviewed journal articles. The sessions are also intended to strengthen the following competencies: a) communication skills, b) critical thinking skills related to the review of scientific methods, statistical analysis of data, and understanding the impact of results on clinical care, c) improvement of reading habits, d) strengthening of collegial relationships via team discussion and analysis of information, and e) development of professional identity that is, “the relatively stable and enduring constellation of attributes, beliefs, values, motives, and experiences in terms of which, people define themselves in a professional role.” 16

The organization of the Journal Clubs mirrors the team structure of each College Class, that is, ten students per college room divided into two teams of five students each. In each two-hour Journal Club session, each of the two teams from one college presents a journal article. Students in the first year select an article from the provided list of approved journals and submit it to their college mentor for approval, thus promoting “self-directed learning with guidance.” In contrast, second year students choose articles on their own, with their selection being evaluated by the college mentor only at the time of presentation, thus promoting “self-directed learning.” The journal reference for both articles must be made available to the entire class and college mentors at least two weeks prior to their presentation. Ten students are involved in each Journal Club session. The remaining students are expected to have read both articles and be ready to facilitate the discussion should their names be drawn from the “Journal Club Urn”.

The Journal Club is designed to be a positive educational experience for all participants. Presenters learn to apply sound principles of education including: a) set-ting specific learning goals for the participants and b) structuring their presentation to address specific information that they want participants to learn. Presenting teams review the article being presented, dividing the presentation evenly among the five team members so that each is responsible for a maximum ten-minute presentation that includes: (a) the introduction (b) materials and methods (c) results (d) conclusions (e) discussion. Each member of the team is expected to be familiar with the entire Journal Club presentation and, therefore, be prepared to present any of the five sections. Prior to the presentation, the college mentor will determine the pairing of the student with the specific “section” to be presented.

3.4. Clinical Skills (CS)

Clinical Skills are longitudinal courses that extend throughout the first two years of the curriculum and are integrated within each system-based course. They are held once each week for two hours. Figure 3 identifies the location of the course in the week’s academic calendar. The courses are designed to teach medical students the basic clinical skills needed for the practice of good medicine. These skills include effective communication, the appropriate application of algorithm-driven history taking and physical examination, the performance of basic procedures, the ability to interpret fundamental diagnostic studies, and fluent, concise, and effective presentations of clinical cases. The Clinical Skills sessions that take place within each course are designed to teach the basic clinical skills that relate to both the covered clinical presentations and to the specific topic of the system-based course. This integration reinforces each component of the course by broadening and deepening the learning experiences of the students.

Another component of the Clinical Skills Courses is a “Service Learning” experience, defined as, “a teaching and learning strategy that integrates meaningful community service with instruction and reflection to enrich the learning experience, teach civic responsibility, and strengthen communities.” 17 Service learning takes place in the local community, and students are involved for one day every three to four weekends over a two-year period.

The scheduled Clinical Skills weekly meetings are divided into three equal sessions, each lasting two hours and accommodating one-third of the class (refer to figure 3 for the location and distribution of the sessions in the week’s academic calendar). Each session is further subdivided into two “stations”, lasting one (1) hour each. These sessions are related to (a) the learning of a practical skill and (b) role playing a problem that presents with the week’s clinical presentation topic.

a. Practical Skills

“Station 1” refers to performing a learned practical skill, either on a manikin, a fellow-student or a standardized patient. Table 4 shows an example of representative activities taking place in the two stations. Performance of each clinical skill is supported by an instructional guide. However, students first observe performance of each skill by the instructor, prior to being allowed to perform it themselves.

b. Role-Playing

Arriving at an accurate diagnosis is critical, and involves carefully evaluating the facts obtained from taking a complete history, performing an accurate physical examination and properly interpreting laboratory study results. According to careful reviews of this procedure, the history contributes approximately 80% (range 64 – 83%) to making medical diagnoses when physicians were involved18-22 and approximately 64% when students (58%) or residents (70%) were involved.22,23 The remaining percentages were almost equally distributed between the physical examination and the results of laboratory tests. The data clearly indicate that taking an accurate “history” is the most important factor in re-aching an accurate diagnosis; however, in today’s time-limited environment it is probably not used effectively. Based on this information, CalMed-SoM is committed to improving history-taking skills, in addition to having students understand their importance. Role playing is a major pedagogical tool in acquiring this valuable skill.

In “Station 2” students employ “role-playing” techniques to enact the clinical presentation problem for that particular week. Each student is pre-assigned a specific “disease” whose presenting complaint is the topic of that particular session. Students are not informed be-forehand what role they will be assigned. Therefore, to be prepared, they must learn their assigned “disease” completely, so they are able to answer all relevant questions asked by the student who will be playing the “physician” in an actual history-taking session. Students who are the “physicians” also need to learn the use of the algorithm and history-taking skills to conduct these sessions. Since students do not know if they are going to be patients or physicians, they are expected to learn both roles!

Being a “patient” is a vital lesson for students. No longer are they simply “learning to learn” in order to treat others, they are given an important opportunity to understand, with more depth, how the “others,” that is, the patients, feel. It is a subtle way to help students understand the best way to elicit important, critical information in order to make an accurate diagnosis. Student patient-physician pairs are assigned their roles randomly just prior to their role-playing. The student playing the role of the physician is unaware of the disease or condition that her/his patient will be simulating. Each role-playing session takes place in a room monitored by a faculty member. At the end of the exercise, a debriefing is held that includes a discussion with the two students based on their compilation of both a “SOAP” note (“SOAP” is an acronym for Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan and refers to a method of documentation employed by health care providers to write out notes in a patient’s chart) by the student playing the role of the physician, and an evaluation form, by the student playing the part of the patient. The role-playing is recorded and reviewed by faculty and the participating students.

3.5. Laboratory Sessions

A challenge for this active-learning, system-based, team-driven curriculum, with its tightly integrated clinical presentations, was the need to create laboratory sessions compatible with the active learning methods used. With this in mind, CalMed-SoM designed the laboratory experience as a hands-on multidisciplinary learning ad-venture in which pre-clinical students are immediately exposed to the integration of structure and function with pathology and clinical conditions from the first day of medical school. Four-hour laboratory sessions are held weekly. Although the majority of the sessions deal with anatomy and related disciplines, including embryology and histology, other disciplines, such as pathology and microbiology, are also covered.

The recent inclination to decrease course hours during medical school has resulted in a significant decline or, in some cases, elimination, of dissection time in human anatomy courses.24 This has resulted in great concerns, including questioning of the effectiveness of the current, more technological approaches to teaching anatomy. The concerns are valid. Not just because of their negative impact on a student’s knowledge but also on the neglected opportunity to reflect on humanity and mortality as well as eroding the human responses of empathy and compassion, important traits for acquiring competence as a physician.25,26 In an attempt to improve long-term retention in the knowledge of anatomy and, to simultaneously allow the student to experience some of the realities of life and death, CalMed-SoM has designed a blended laboratory experience, using both cadavers, as well as anatomical-imaging correlations, anatomical characterizations of surgical procedures, ultrasonographic living anatomy sessions together with pathological correlates. This approach in the teaching of laboratory procedures allows anatomic, physiologic and pathologic principles to be appreciated and applied to the clinical concepts taught during the CPs and the clinical cases of CalMed-SoM’s active learning curriculum.

To achieve this goal, students are divided into small groups, each of which rotates for one hour through four different laboratory stations. The content of the stations is integrated into the current CP learning topic of that week by presenting its gross anatomy, procedural anatomy, ultra-sonographic and imaging components as indicated in Table 5: A and B.

The Faculty at CalMed-Som believe that this active learning approach in the laboratories will be effective in enhancing the ultimate learning experience and professional acumen of its students. As designed, it will improve the early knowledge and skills acquisition of medical students, better preparing them to meet the challenging diagnostic and safe practice requirements needed for the clinical experiences in their clerkship years. The performance of bedside procedures, in addition, will promote and reinforce the “spiral” integration of the basic and clinical sciences within the curriculum.

3.6. Academic Research Study (ARS)

CalMed-SoM’s commitment, to both its students and to the field of medicine, is to provide students with experiences in research, encouraging them to understand its importance to the successful practice of medicine as well as the stimulating, creative aspect of doing research. CalMed-SoM recognizes that real research is not a hobby or a side activity, and that going through the educational program to become a physician is very demanding. However, it is realized that understanding research and being able to accurately assess its conclusions is an essential factor in good medical practice. For this reason, CalMed-SoM has designed a mandatory, basic course in research for all students. It also strongly encourages its students to supplement this course with appropriate research electives in order to enhance the research experience and encourage a more in-depth appreciation of the necessity of life-long learning and critical thinking.

The Academic Research Study Course takes place throughout the second year. Although the course is a mentor-guided research program, by the end of the course the student is expected to lead the project and demonstrate independence. The course itself is pre-ceded by a one-week introductory session at the end of the first academic year. This introductory session is designed to serve a dual purpose: a) to provide basic, essential information on how to approach and conduct a successful research project, and b) for those students who would like to pursue research interests in conjunction with Global Health, the introductory session will also provide adequate preparation to do so. In addition, the course encourages students to undertake research activities during the summer respite.

VI. Clinical Years

In the third and fourth years of the curriculum, students rotate through a series of clinical clerkships, sub-internships, and electives. During these rotations, students are placed both in inpatient and outpatient set-tings, working closely with faculty, resident physicians, and other members of the healthcare team. The clinical rotations including clerkships, sub-internships, and electives, allow students to apply their knowledge of the basic sciences and expand their clinical knowledge and skills in the fields of surgery, internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics & gynecology, neurology, psychiatry, emergency medicine, and the subspecialties within these major medical disciplines. Key scientific principles are reinforced during these years to complete the vertical integration of basic science information.

Year 3

During the third year of the curriculum, students rotate through seven different disciplines, contained within six blocks, each block lasting eight weeks, as denoted in Figure 5 and Table 6. During the clinical rotations, the students have the opportunity to recall and refer to the “clinical presentation” algorithms that were introduced in the first two years, thus fully integrating the educational experiences throughout the curriculum.

Year 4

The fourth year of the curriculum is composed of nine blocks, each lasting four weeks, for a total of thirty-six weeks. During this year students are allowed to choose one of four “Paths,” i.e., surgical, medical, service, and customized, as indicated in Table 6, which reflect each student’s future goals. Each Path lasts twenty weeks and is composed of three preparatory courses, each lasting four weeks, designed to prepare students for their chosen eight-week, sub-internship as well as their future aspirations. In addition to the chosen Path, students are also required to select up to four electives, one of which must be in Emergency Medicine. For the remaining electives, students are strongly encouraged to diversify their preferences by choosing at least one from each of the following three categories: career-oriented clinical disciplines, including focused experiences in the intended specialty non-career oriented clinical disciplines, which indicates experiences not directly related to an intended specialty service-oriented disciplines referring to structured service learning experiences in the field of Global Health/Public Health with emphasis on local, national or international resource-challenging settings.

- Surgical Path: (see table 6)

The surgical path begins with three, four-week courses, before an eight-week sub-internship, that includes (a) the anatomic and cadaveric dissections of areas of the body related to the a student’s sub-specialty aspirations, (b) participation in a surgical pathology laboratory where the student reviews macroscopic and microscopic surgical specimens, and is involved with the autopsy service (c) diagnostic imaging, focusing on all forms of imaging studies, in particular those related to a chosen sub-internship. In this Path, the student can select one of two sub-internships: General Surgery or Obstetrics and Gynecology.

- Medical Path (see table 6)

The Medical Path contains two, four-week courses, preceding an eight-week sub-internship. One of the two courses, Basic Science Update, is a capsule review of specific topics in basic science disciplines most frequently encountered in the practice of medicine. The second course is a rotation in the diagnostic imaging department. In this Path, the student may choose one of two sub-internships: Internal Medicine or Pediatrics. After completing the sub-internship, students are also required to take a four-week elective related to the chosen sub-internship, in addition to three other general electives.

- Service Path: (see table 6)

The Service Path contains two, four-week courses, before an eight-week sub-internship. The two required courses are similar to those of the Medicine Path. Stu-dents may choose one of three sub-internships: General Surgery, Internal Medicine or Pediatrics. After completing the sub-internship, students may take electives rela-ted to the field that they plan to pursue.

- Customized Path: (see table 6)

The Customized Path requires that students take the Emergency Medicine clerkship and one of the four available sub-internships: General Surgery, Internal Medici-ne, Pediatrics or Obstetrics and Gynecology. Courses necessary to complete the required 36 weeks, may be from any of the three categories indicated above (see section “B. Year 4”).

VII. Assessment methods

The purpose of assessment is to ensure that students are developing the required level of competence in knowledge, skills and attitudes for the practice of medicine in a supervised setting. The principles that have guided the development of CalMed-SoM’s assessment plan include the following convictions:

- The recognition that: a) medical students are responsible, motivated adults and are therefore expected to participate actively in assessing their own learning progress, guided by staff, fellow students, patients and others; b) the assessment process should en-courage and acknowledge co-operative learning and excellence and be clear, so that students know in advance what they need to do to pass or obtain better results in a course; and c) the Faculty has a responsibility to assure students, staff, the profession and the public that graduates have achieved the prescribed institutional outcomes to become physicians.

- The conviction that assessments should: a) support learning and promote the integration and application of information, principles, and concepts; b) closely match “real-life” situations whenever possible; this should include frequent observations of students interacting with patients; and c) use a combination of methods to provide a comprehensive assessment of the core knowledge, skills, and attitudes defined in the institutional program outcomes for the medical degree.

- The number, timing, and weighting of individual assessments are designed to maximize validity (both formative and summative).

- Both formative and summative assessments will test and evaluate knowledge, skills and attitudes that are defined in the learning outcomes for courses and clerkships in the curriculum.

- The formative (learning) functions of assessment will be given as much emphasis as the summative (grading and selection) functions.

Formative Assessments

Frequent assessments enhance student learning.6,7 The more opportunities students get to work actively with course material and receive feedback, the better the chances that they will learn and retain it.9 Formative assessments are designed to monitor student learning and provide ongoing feedback that can be used to improve both learning and teaching. These forms of assessments are informal and intended to (a) make students aware of their learning progress, help them identify their strengths and weaknesses, and thereby target areas that need modification or additional work, (b) help the faculty recognize where students are struggling and address these problems appropriately and in a timely manner, (c) provide regular feedback and evidence of progress, (d) alert instructors about student misconceptions, (e) serve as an “early warning signal,” (f) allow students to build on previous experiences, (g) align with instructional and curricular outcomes, and (h) portray student’s life as a learner. Through the use of formative assessments, information about students’ progress is accumulated and used to help make instructional decisions that will improve learning and achievement levels. The formative assessment methods used to assess the six institutional competencies are indicated in Table 7.

Summative Assessments

These assessments are intended to be a formal process that evaluates student achievement of the learning outcomes of a course or clerkship throughout the four-year curriculum. They serve to determine student mastery and understanding of information, skills, concepts, and processes, and will be used to reach decisions regarding grade reports, student progression and exit achievement. The results of summative assessments will contribute to the final result in a course or clerkship.

A detailed explanation of the various assessment methods used in the different courses at CalMed-SoM is beyond the scope of this article. Formative and summative assessments methods used to evaluate the institutional competencies encapsulated in CalMed-SoM’s Program Learning Outcomes are summarized in Tables 7 and 8 respectively.

VIII. Conclusions

CalMed-SoM, the new medical school in Southern California, is being designed as a socially accountable school that will advance medicine by an innovative, carefully honed medical education program. Medical education at CalMed-SoM is student-centered, incorporating an innovative curriculum that includes an amalgam of established, successful pedagogy, collated from the most advanced educational institutions throughout the world. This curriculum promotes a team-based educational strategy that enhances and refines the potential practice of medicine as students learn to collaborate, to analyze, to express themselves and, above all, to under-stand that it is not the fastest answer that is necessary but the answer grounded in careful listening and careful analysis. This competency-based curriculum, designated as the “Global Active-Learning Curriculum,” incorporates carefully conceived approaches and methodologies to learning, guided by adult learning strategies. It is clinical presentation driven and utilizes a Person-Centered Clinical Approach Learning Method. This Method refers to a structured, guided inquiry technique that enhances a student’s ability to understand disorders, problems, and clinical cases. Through team participation, students integrate relevant basic science knowledge with clinical knowledge acquired through self-directed learning strategies and, using analytical and critical thinking skills, that include understanding the clinical relevance of all the scientific, environmental and social determinants relevant to the clinical problem, find appropriate answers to profound questions.

CalMed-SoM’s clinical presentation-driven curriculum helps students identify their strengths and weak-nesses, allowing them to draw on the former and rectify the latter, as they assume responsibility for their own learning and build the foundations for a lifetime of learning and self-improvement in aspiring to be competent and caring physicians with leadership skills for the complex world of the 21st Century.

Table 1: Names used for 1st & 2nd yr courses (in parenthesis are indicated the equivalent traditional system names). *Medicine being “Art and Science”, the title denotes the principles of that part of medicine that is “Science”-related **Running simultaneously throughout the system-based courses of the respective academic years.

Figure 1: Courses of the first (A) and of the second (B) academic years. The numbers in each of the colored rectangles indicate the length, in weeks, of each course. The sequence of the courses in the two academic years is indicated by the progressive number (i.e. 1st, 2nd, etc.) found in the white rectangles and their titles can be found in Table 1.

Figure 2: Exam week composed of review time during the first 3 days and exams on the last two days of the week.

Figure 3: Typical week of educational activity. The grey-shaded blocks are times set aside for individual student or team-related activities which comprise 37.5% of total week hours. For a description of the individual educational activities indicated in the figure, which comprise 25 hours of contact hours, see text. Note: The two discussion sessions, appearing both on Wednesday and Thursday (indicated as “(B)”, are to be considered as a single session even if interrupted by a “lunch” break. The letters “A”: through “N” contained within the Classroom Discussion Session boxes, refer to the sequence of topics found in table 2.

Table 2: Example of 1 week of prepared, voice-over PowerPoint lectures to which the student has access at least 2 weeks before they are discussed in class. Four lectures (sequence A – D) will be covered in the 4 hr Monday discussion session and five lectures in each of the 4.5 hr Wednesday (sequence E – I ) and Thursday (sequence J – N) sessions.

Figure 4: Algorithm on “weight loss” represents the first clinical presentation in the course “The Scientific Foundations of Medicine”.

Table 3: Items that need to be addressed by students from each team in the presentation of their clinical case during Small Group Session 2 on Friday. Each student should be familiar with the entire clinical case and be ready and prepared to present any of the five items. Pairing of the student with the item to be presented will occur at the discretion of the presiding College Mentors, just prior to the presentation.

Table 4: Schedule showing the integration of the Clinical Presentations with the Clinical skills sessions, along with the schedule for the College colloquium and Journal Club sessions, for the course entitled “The Structural Integrity of the Human Body”

Table 5: Excerpt of the laboratory schedule from the first course of year 1, “The Scientific Foundations of Medicine” (A) Content of week 1 of the course, and (B) content of week 5 of the same course

Figure 5: Schedule showing the 8 week block rotations of the various clerkships composing the third year of the CalMed-SoM curriculum.

Table 6:(A) Year 3 curriculum indicating the Clerkships and their duration in weeks. (B-E) Year 4 curriculum indicating the four different Paths available to students, i.e. Surgical Path (B), Medicine Path (C), Service Path (D), and Customized Path (E) *At least one (1) of the electives must be related to the sub-internship selected (Surgery, Medicine, Pediatrics, or Obstetrics & Gynecology).

Table 7: Formative Assessment methods used to assess the six Institutional Competencies

Table 8: Summative Assessment methods used to assess the six Institutional Competencies.